As namers, we use words like “neologisms,” “hybrids,” and “current usage words” with every project we work on. A neologism (from the French “new + body of knowledge”) is a made-up word or something that has been coined for a specific purpose (ex: Aceba). A hybrid is two words fused together (ex: FunHub), while a current usage word is something you would find in the dictionary.

If you think about it, every word was at one point in time a neologism, a new word, something that someone made up. Someone had to fabricate it somewhere in history. Words become interesting parts of our vernacular when we have an association that gives them a new definition.

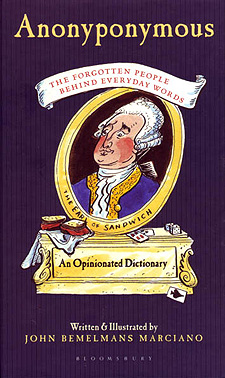

Anonyponymous: The Forgotten People Behind Everyday Words by John Marciano hits the shelves today, and takes a different approach at examining the origins of current usage words. Coining a word himself, John fuses “anonymous” with “epononym” to introduce a new word into our vocabulary; “anonyponymous” refers to eponyms that were created based on otherwise anonymous people in history. It provides some fascinating references to very obscure people (and moments) in history.

Here’s a sneak peek:

jum·bo adj. Enormous; huge; really, really big. One fine morning in 1861, a little elephant awoke expecting to spend another day munching grass on the sunny savanna. Alas, he never would again. Captured by exotic animal traders, the unwitting pachyderm was shipped off to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, where he spent the unhappy remainder of his calfhood. Skinny, sickly, and only four feet tall, he was unceremoniously swapped to the London Zoo for a rhinoceros. Named Jumbo by his new zookeeper — it kind of sounded African — the elephant began to grow. And how could he not? His daily menu included 200 pounds of hay, two bushels of oats, 10–15 loaves of bread, a barrel of potatoes, a bunch of onions, and many, many barrels of water, with an additional one of whiskey or ale on occasion, for his health. Who says you eat better in Paris than in London? Jumbo, now enormous, became a hit with the crowds. He’d snatch up coins and peanuts in his trunk and give rides to the kiddies for pocket change, including a couple of young tykes named Winnie Churchill and Teddy Roosevelt. And then a man took a ride on his back who knew he could charge a whole lot more than a few measly shillings for the Jumbo experience.

In 1881, Phineas T. Barnum expanded his circus from two to an unprecedented three rings. Needing a star, P. T. went out and bought seven tons of one. The outrage across Britannia was immediate and intense. Schoolchildren wrote letters of protest to Queen Victoria, who herself was outraged but couldn’t do anything to reverse the $10,000 sale. The London Daily Telegraph bemoaned how poor Jumbo would have no more shady walks in the park, and instead be forced to “amuse the Yankee mob.” The controversy resulted in a publicity bonanza for Barnum, who billed Jumbo as the largest elephant in the world. America was seized by Jumbomania. Every product imaginable was called Jumbo. There were Jumbo cigars, Jumbo trading cards, Jumbo fans — if something was big, it was Jumbo-sized! The new attraction sold over a million dollars in tickets for Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth in the first year alone.

For Jumbo, stardom wasn’t that great. In a self-destructive burst reminiscent of so many later celebrities, Jumbo ran wild one day in Canada and was killed by a train. Some say he was drunk, and others that he was in a blind rage, while Barnum, ever the master of spin, claimed Jumbo had been struck down while bravely rescuing a baby elephant, pushing the little fellow out of the way of the locomotive at the last instant.

Friends, family, and clients often ask me for the backstory of the brands we create. Now I can throw in a little extra trivia on the origins of the words we use every day. Thanks John!